And the Wise Man Said: Show Me the Money

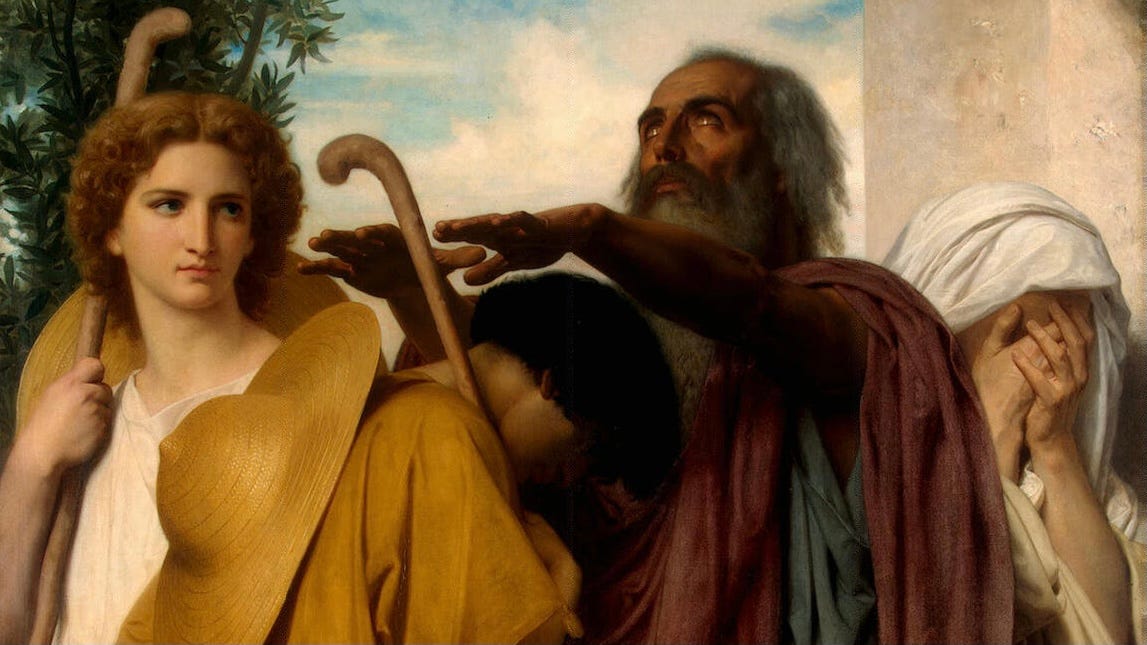

As Tobit prepares to die, he remembers a treasure left years ago in another city! How should he prepare his son to retrieve it? Tobit 4.1–5.3.

Episode 4 of “Bad” Books of the Bible is live. Listen at Ancient Faith Radio or wherever you get your podcasts. And help others find out about the show by sharing it and leaving a rating or reviews.

Praying the king’s prayers

In the last episode we talked about the prayers of both Tobit and Sarah. At the start of Episode 4 we reflect on how surprisingly personal these prayers are. They seem to capture a freeze-frame moment in Israel’s spiritual evolution. We can see that by contrasting present-day practices with times prior to Tobit and Sarah.

Christians today possess Bibles, psalters, and prayer books. The content of those books inform how we pray. We can either adopt those words as our own, verbatim, or improvise new prayers based on what we learn in their pages. Some Christians approach prayer with improv as the primary method employed; as one writer put it, “No Christian should need a manuscript to pray!”1

But ancient Israelites didn’t own Bibles, psalters, and prayer books, and Old Testament prayer does not usually seem spontaneous and original with the petitioner. Prayer was not the personal initiative of individuals. Rather, it was the corporate offering of peoples, tribes, and the nation—usually at various shrines or the temple, often by or for the king.

The development of the psalter bears this out. “The Hebrew psalms,” writes biblical scholar James Kugel, “seem to have been intended for recitation at one or another of Israel’s ancient sanctuaries, either by a choir or an individual, and in either case presumably as a complement or accompaniment to the offering of sacrifices.” While they may sound like prayers arising out of singular situations, these are, he concludes, “liturgical compositions” primarily for use at various shrines or the temple.2

With the rise of the monarchy, the king was seen as the key petitioner. “Prayer was an essentially official, not personal, matter,” writes biblical scholar Paul Tarazi, who notes that people typically conceived of the divine in tribal, not personal terms.3 Surveying the psalms in his History of the Bible, John Barton demonstrates how seemingly individualized petitions are still often intershot with corporate language and kingly themes.4

Not only are many of the psalms explicitly presented as royal psalms, but the final edited collection is framed as the prayer book of the king. It begins with the kingly duo, Psalms 1 and 2, and closes (in the Septuagint) with Psalm 151, a first-person account of David’s early life and victory over Goliath. (Yet another “bad” book of the Bible we’ll eventually cover.)

Your words shall be my words

There are very few examples of prayer in the Old Testament that would counter this general argument. The prayer of Samuel’s mother, Hannah, for instance, has every indication of a cut-and-paste prayer offered at a shrine per the above. While her particular concern is childlessness, that occupies only one couplet in the entire prayer. Hannah’s prayer has what Kugel calls a “one-size-fits-all” quality like many other prayers in the psalter.5

Tarazi compares this feature to greeting cards, wedding toasts, and funeral elegies— standardized, general language available for individual use.6 This is speculation, but we can imagine the priest or one of his helpers having a collection of prayers to work with and giving Hannah this one because of the “keyword match” with barrenness. It might have been the most subject-matter-appropriate prayer “on file.”

Another possibility is the author of 1 Samuel, working from the palace archives, had the prayer on file and included it as he composed the book, again because of the keyword match. Tellingly, Hannah closes her prayer not with reference to her own plight but the welfare of the king. That seems odd in her prayer when considered solely as her personal, self-generated petition but very appropriate when we consider her story as the introduction to a book about Saul and David.7

Individual concerns

Taken together, we see the prayer life of ancient Israel as liturgical, corporate, and top-down. But there’s something new happening in the prayer of Tobit and Sarah. The Book of Tobit is composed after the psalter is collected and edited. There has been time for its use to permeate and evolve, shaping the prayer habits of ancient Jews, especially as believers were forced in the diaspora to pursue spiritual life outside the temple.

In Tobit and Sarah we see people who have incorporated the sentiments and spirituality of the psalter for personal petitions. They don’t close on the king’s concern, like Hannah; they close on their own concerns. But the language is nonetheless elevated and formal, even following a set pattern:

invocation/adoration

supplication/petition

explanation

restatement of petition8

So we see in Tobit and Sarah a bridge between Hannah’s prefab, top-down prayer and the kind of personal, autonomous, bottom-up prayer we’re more familiar with. And this is part and parcel of the whole Second Temple period.

Something new in the Second Temple period

With exile and the subsequent destruction of the Temple, the top-down nature of the old Israelite political and religious system was shaken. Because of the need to practice the faith in exile—and perhaps under the eventual influence of more individualistic Greek culture—Judaism became “democratized,” that is, focused more on individual concerns and responding more to individual initiative. In this period, as one example, purity standards expanded beyond the priestly class to include all observant Jews.9

Personal piety received far greater stress following the exile, and personal piety like Tobit’s became exemplary and championed. Beyond the claims God makes on the people of Israel, it’s increasingly clear that he makes those claims on individual Israelites as well. As a result, there’s an increased emphasis on judgment and messianic hope, along with a growing belief in personal resurrection.10

As with the development of personal prayer, the Book of Tobit gives us a picture of this transformation as it happened. Most of the Old Testament narratives focus on key figures—patriarchs, rulers, prophets, people with whom the nation’s fate is bound. While it’s possible the Book of Tobit was written under the patronage of the Tobiad family, a powerful family in the Second Temple period, Tobit himself is not a grand or important figure and neither are Sarah or Tobias. The narrative instead invites us to see the struggles of God’s people not through the life of a king or sage, but a few ordinary Israelites. The book represents a snapshot of Judaism’s change toward an increasingly individualist expression.

And where does that leave Tobit, Sarah, Tobias, and everyone else in our story? Personal concern is exactly where our story left off, and there’s nothing more personal than money. The problem is that Tobit has none.

Except, he does!

Under the couch cushions in Media (Tobit 4.1–2)

The same day he prays to die, Tobit remembers a stack of cash he left in Rages, which is in Media. For the details, jump back to chapter 1. Tobit was Shalmaneser’s agent, and in that role, he left a bag of 10 silver talents in Media. How much money are we talking about here? Well, one drachma equates to a day’s worth of manual labor. One talent is worth about 6,000 drachmas. Back of the napkin calculation: They’re rich!

Why did it take till now for this money to come up? During Sennacherib’s reign, the roads were unsafe so Tobit never went back for the cash. He evidently wrote off the money. But now it’s twenty years later. Senacherib’s gone, the roads are clear, and there’s a chance to retrieve the cash.

And the clock is ticking. Tobit has prayed to die, and he has every confidence God is going to answer that prayer with a yes and do so soon. “Now I have asked for death. Why do I not call my son Tobias and explain to him about the money before I die?”

So he calls Tobias. But curiously, he doesn’t start by telling him about the money. Instead, he starts by giving him formal life advice in what scholars call a testament.

Do this, not that (Tobit 4.3–11)

Tobit rattles off a long list of do’s and don’ts, most of which have already been exemplified by himself in the story thus far. He instructs Tobias to bury him when he dies and do the same for his mother, being sure to not grieve her in the meantime.

He tells him to revere the Lord and follow his commandments because “those who act in accordance with truth will prosper in all their activities.” We can only wonder what Anna and Tobias think when they hear that, given Tobit’s current low state.

Then again, maybe Tobit had that in mind because he moves on to address the importance of charity: “To all those who practice righteousness give alms from your possessions. . . . Do not turn your face away from anyone who is poor. . . .”

Jesus echoes this very line in the Sermon on the Mount: “Give to him who asks of you, and do not turn away from him who wants to borrow from you” (Matthew 5.42 NASB). As he often does, Jesus here biggie-sizes the Old Testament commandment. His statement is more universal, no longer conditioned by practicing righteousness; people need only ask.11 It’s also just one of many Apocryphal echoes heard in the New Testament.

Giving in proportion to means, laying up treasure, the day of necessity, and alms saving from death are all themes of which New Testament writers, readers, and audiences would be well aware. And they’re all clustered here in chapter 4 of Tobit, anticipating Jesus, St. Paul, St. James, and the rest of the voices with whom Bible readers are generally more familiar.

Tobit’s testament mirrors Old Testament wisdom literature, bringing to mind Proverbs and Sirach (another “bad” book we’ll cover). The church fathers naturally mine Tobit for sage advice and models of practical holiness. For example, the second-century martyr and disciple of the apostle St. John, Polycarp, picks up his advice on almsgiving in his Letter to the Philippians: “When you can do good, defer it not, because alms deliver from death,” a direct quote from Tobit.12

Marry a nice Jewish girl (Tobit 4.12–13)

Tobit then shifts to advice for marriage. He tells Tobias to flee fornication, though scholars here say the advice goes beyond premarital sex. Tobit’s concern is a major concern of many postexilic Jews—the threat of intermarriage to Jewish identity. The advice is, in so many words, “Marry a nice Jewish girl.” Driving home the point, Tobit mentions the example of “Noah, Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob,” forebears who “all took wives among their kindred.”

Where does he get that insight? Genesis yields the details for Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob’s stories. But what about Noah? The first book of the Bible says nothing of the matter. Interestingly, another book does. Once colloquially known as Lesser Genesis or Little Genesis, the apocryphal Book of Jubilees dishes on Noah.

“In the twenty-fifth jubilee,” it says, “Noah married a woman whose name was Emzara, the daughter of Rakiel, the daughter of his father’s brother” (Jubilees 4.33). For what it’s worth, the Ethopian Orthodox Church regards Jubilees as canonical.

Deal straight and don’t be a jackass (Tobit 4.14–19)

Tobit’s advice is all geared toward helping Tobias live in exile while maintaining an identity as a faithful Israelite; it’s advice readers in the diaspora would have valued and followed. Practicing charity and avoiding fornication were key parts of Jewish identity. So was dealing straight—that and a grab bag of final advice fill the remainder of Tobit’s testimony.

Don’t cheat your employees

Be self-disciplined

Don’t overdo the booze

Feed the hungry

Clothe the naked

Don’t give begrudgingly

Consult the wise

Pray that God prospers you

The most interesting line item in Tobit’s litany is what writer Nassim Nicholas Taleb calls the Silver Rule, the inverse of the Golden Rule. “What you hate, do not do to anyone,” says Tobit. As a child, I (Joel) often heard the Golden Rule in the negative—as a warning—but it’s interesting to have it stated here as such. While the Golden and so-called Silver Rule are both ancient and appear all over, Tobit’s injunction here seems to be the earliest statement of the Silver Rule in the West.13

The fathers saw this instruction of Tobit’s as being exemplary, even salvific. St. Cyprian of Carthage encouraged parents to emulate Tobit. “Be . . . such a father to your children as was Tobit,” he said. “Give useful and saving precepts to your pledges, such as he gave to his son; command your children what he also commanded his son.”14

And St. Augustine, alluding to Tobit’s blindness, said, “The son held out his hand to his father, to enable him to walk on earth; and the father to the son, to enable him to dwell in heaven.”15

All of this matters all the more given the shift to personal holiness mentioned above.

Show me the money! (Tobit 4.20–5.3)

With such elevated thoughts, it might seem crass to bring it back to money, but as another wisdom book put it, “money meets every need” (Ecclesiastes 10.19). And Tobit’s family was definitely in need.

Having given him moral and ethical instruction, Tobit tells Tobias about the cash in Media. “Do not be afraid, my son, because we have become poor. You have great wealth if you fear God and flee from every sin and do what is good in the sight of the Lord your God.” The implication is that the money is conditional. The purse exists, but possession is contingent on faithfulness.

Tobias is in. “I will do everything that you have commanded me,” he says. The two talk about logistics—where the money is, how to retrieve it—and Tobit enjoins his son, “Find yourself a trustworthy man to go with you, and we will pay him wages until you return. But get back the money. . . .”

And so the journey soon begins.

Useful quotes

Theron Matthis on the saving potential of almsgiving:

Almsgiving delivers from death because it is an act of crucifixion. It is an embrace off the cross in which you are to die to yourself, unite with the Author of life, and experience resurrection. Yet almsgiving is not cruciform if done selfishly or begrudgingly; it must flow from a heart of sacrifice and trust in the Giver of life.16

Nassim Nicholas Taleb with his take on the Silver Rule:

The Golden Rule wants you to Treat others the way you would like them to treat you. The more robust Silver Rule says Do not treat others the way you would not like them to treat you. . . . It tells you to mind your own business and not decide what is “good” for others. We know with much more clarity what is bad than what is good.17

Pope St. Gregory the Great on the complementarity of the Golden and Silver Rule, which he referred to as “two precepts of both Testaments,” indicating his regard for Tobit as canonical.

By the one an evil disposition is restrained, and by the other a good disposition charged upon us, that every man not doing the ill which he would not wish to suffer, should cease from the working of injuries, and again that rendering the good which he desires to be done to him, he exert himself for the service of his neighbour in kindness of heart.18

Coming next week

You may recall our references to Media before. It’s where Sarah lives. The money is the McGuffin that nudges our two storylines together. Next week, Tobias meets a stranger and begins a journey to recover the treasure in Media. He will return with more than he bargained for—but you knew that, right?

In the meantime, consider sharing the show or leaving a rating/review wherever you get your podcasts.

Brian Davis, “How to Keep Your Spontaneous Prayers from Sounding Aimless and Shallow,” 9Marks, June 21, 2016.

James L. Kugel, The Great Shift (Mariner, 2018), 132–133.

Paul Nadim Tarazi, The Old Testament: An Introduction, Vol. 3: Psalms and Wisdom (St. Vladimir’s Seminary Press, 1996), 74.

John Barton, A History of the Bible (Viking, 2019), 116–126.

Kugel, Great Shift, 134.

Tarazi, Old Testament, Vol. 3, 73.

Robert Alter presents this possibility in The David Story (Norton, 2000), 9. See also Tarazi, Old Testament, Vol. 3, 72.

Adapted from Bruce M. Metzger, An Introduction to the Apocrypha (Oxford University Press, 1977), 39.

Eyal Regev, “Pure Individualism: The idea of non-priestly purity in Ancient Judaism,” Journal for the Study of Judaism 31.2 (2000). See also Daniel Boyarin, The Jewish Gospels (The New Press, 2012), 115.

See Shaye J. D. Cohen, From the Maccabees to the Mishnah. 3rd Ed. (Westminster John Knox, 2014). John Merlin Powis Smith, “The Rise of Individualism among the Hebrews,” The Journal of Religion 10.2 (April 1906).

David A. DeSilva, The Jewish Teachers of Jesus, James, and Jude (Oxford University Press, 2012), 94.

Polycarp, Letter the the Philippians 10.

DeSilva, The Jewish Teachers, 96.

Augustine, Sermon 38 on the New Testament 16.

Theron Matthis, The Rest of the Bible (Conciliar, 2011), 35.

Nassim Nicholas Taleb, Skin in the Game (Random House, 2018), 19.

Gregory the Great, Moralia in Job 10.8.